![[ Table of Contents ]](../gx/indexnew.gif)

![[ Front Page ]](../gx/homenew.gif)

![[ Prev ]](../gx/back2.gif)

![[ Linux Gazette FAQ ]](./../gx/dennis/faq.gif)

![[ Next ]](../gx/fwd.gif)

"Linux Gazette...making Linux just a little more fun!"

Making Smalltalk with the Penguin

A quick tour of Smalltalk

By

Abstract

Since VisualWorks Non Commercial (VWNC) has been freely released for Linux, there's been an increased interest in the Linux community about Smalltalk. The purpose of this article is to give an introduction to Smalltalk for Linux enthusiasts who aren't familiar with it, and to share some of the characteristics of this language that endears itself to so many programmers. There's lots of tutorials and references to Smalltalk out there already. This article isn't intended to be a tutorial or reference for OO programming or Smalltalk, but just a quick tour to whet the palate. General OO knowledge isn't assumed, and the article can be read standalone or while coding-along.

Much of the examples here apply equally well to all implementations of Smalltalk. Though all implementations of Smalltalk share the same basic characteristics, there are differences among them - especially when GUI code comes into play. There's a number of freely available1 Smalltalk implementations available for Linux: GNU Smalltalk, Smalltalk/X, Squeak, and VisualWorks Non Commercial2. Squeak in particular is doing some really cool stuff lately, but the examples here are written in VWNC, since this is the flavour that I'm most familiar with. Also, even though there's a later version available, I'm going to use VWNC v3.0 for illustrative purposes since that is the version with the most freely available tools/extensions available.

This article covers some background information on Smalltalk, getting and installing VWNC3, characteristics of Smalltalk (with examples), and further references. The characteristics of Smalltalk that are covered here are that it:

- is a pure OO environment, encourages OO programming

- can save exact state of the IDE

- is a literate language

- is incrementally byte-compiled

- is a portable environment; write once, run anywhere (virtual machine/ GUI)

- can inspect and manipulate objects in real time

- has a large degree of reflectiveness (start with running app, extensions)

- has garbage collection, no explicit pointers

1.0 Background Information

Little known Java/Smalltalk factoid: the original Oak team wanted to use VisualWorks Smalltalk for their purposes, but ended up inventing Java when the licensing of VisualWorks at that time proved to be too costly for them3.

Smalltalk has been around for quite a while, it originated at the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) in the early 70s, and its original intention was to provide an environment for children to start learning how to program in. Accordingly, its syntax is very simple and it's a very mature environment. Smalltalk's power is rooted in its large class library, which can be a double-edged sword. You don't have to keep reinventing the wheel to get any work done, but on the other hand you spend a lot of time looking for the right wheel to reuse when you're first learning it4.

Another double-edged sword is that it's a pure OO environment, and thus encourages people to make the paradigm shift to OO much more strongly than other Object Based (OB) languages5 (more on this later). People who make the shift tend to become very attached to Smalltalk and find it a very fun, productive6, and theoretically pure environment to work in. People who don't make the shift tend to shun it, and stay in OB languages where it's easier to get away with writing procedural code in the guise of writing OO code. (No Dorothy, just because you're using a C++ compiler doesn't mean that you're writing OO code).

Though many people characterize Smalltalk as only being useful in large, vertical markets, Smalltalk is extremely flexible in that it is also used in very small, horizontal markets. Smalltalk has been used to write applications7 for large network management systems, to hospital clinical systems, to palm pilots, to micro controllers, to embedded firmware.

But that's enough background information, let's get on with some real examples.

2.0 Installation Stuff

VWNC3 can be obtained from a free download site. You need to fill in your name, address, city, state, zip, and email address to proceed. After doing this, when you click the I Accept button, a 20,594 KByte download immediately starts, 'vw.exe'. Not the most user-friendly download mechanism in the world, especially making a Windoze & Linux version both available in a Windoze self-extracting archive, but it works. Download this to the parent directory of where you want it to be, and unzip using unzip vw.exe. The zip file will extract itself into Vwnc3. For myself, I'm running dual-boot, so I downloaded into my /dos directory and unzipped from there so I can also use it from Windoze, giving me a base directory of /dos/vwnc3. (Alternatively, you can specify a VISUALWORKS environment variable with the path).

To start it up, I like to copy the virtual machine to the image directory, or to make a symbolic link. Since I have it installed on my dos partition, I'll make a copy:

cp /dos/vwnc3/bin/linux86/visualnc /dos/vwnc3/image/visualnc

I noticed that the virtual machine isn't executable by default, so let's make it that way:

chmod 555 visualnc

Then to start the image, it's necessary to tell the virtual machine what image to run, do:

cd /dos/vwnc3/image

visualnc visualnc.im

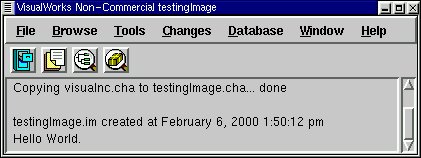

A license reminder screen pops up every time you start VWNC, click I accept, and proceed through it. The window that appears on top is called the Transcript, and the window below it is called a Workspace. Next, you need to inform the image where to find its needed system files. To do this, click on File>Set VisualWorks Home from the Transcript. In the dialog that appears, enter in the home directory: /dos/vwnc3.

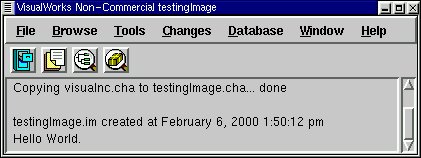

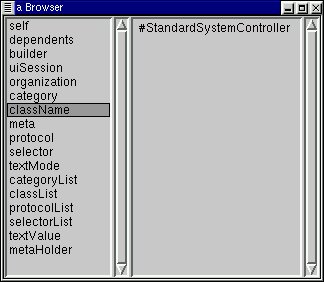

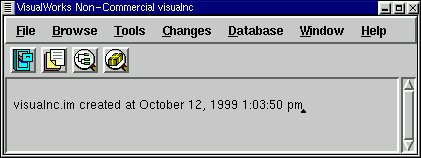

The Transcript and Workspace look like:

Fig. 1 - VWNC Transcript

Fig. 2 - Default VWNC transcript

The startup workspace has some useful information that's worth reading, but it isn't necessary to read it to continue through this article.

A note on mice: Smalltalk assumes that you have a three button mouse. If this isn't the case, you can simulate a three button mouse on a two button mouse by clicking both the left and right buttons at the same time.

3.0 Some Notable Characteristics of Smalltalk

3.1 Saving your work

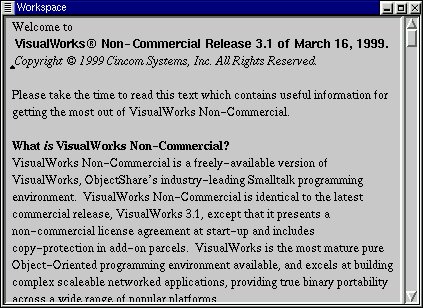

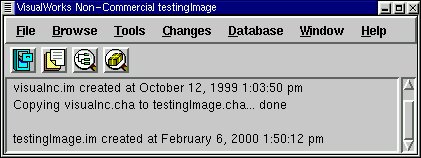

Here's another double-edged sword: the great thing is that when you save your IDE, everything is saved exactly in the state where you left it. What windows you have open, where they were open, what was highlighted, the objects that exist, everything. A snapshot in time is taken and is saved in an image. There's no need to reload a text file into a text editor, and find where you left off. The other edge is that if you have a corrupted database connection or have overwritten some objects you shouldn't have, that's also saved with the image. So there's a need to be cognizant of the state of your environment when saving it. Having said that though, you can save your code separate from the image, and reload it into a clean image if you do run into problems (a good idea to do anyway). A simple way to save your code is in a fileout.

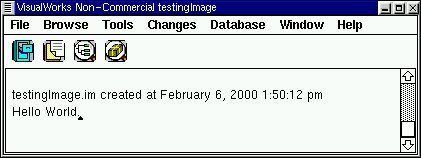

Lets give saving a try (might as well save the system file location you just specified). Move your windows around until they're where you like them, then save your image, select File>Save As... It's a good idea to save your image as something other than the virgin image, so if you run into problems you can always return to the clean image and reload your code. I'll save the image as testingImage. After saving, try closing the image File>Exit VisualWorks...>Exit. Then to restart, be sure to pass the new image name to the virtual machine. Note, that when you save your image, the date and time are printed on the transcript, like so:

Fig. 3 - Transcript after saving as 'testingImage'

There's a lot more I could say here on saving your work (Perm Save As, filing out, change log, Envy), but I'll digress in the interests of brevity.

3.2 Everything is an object

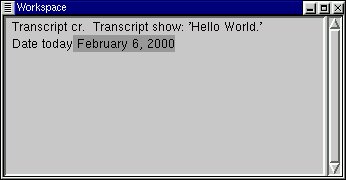

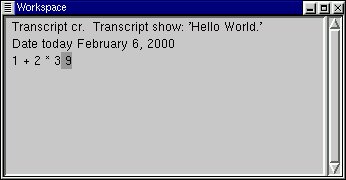

...this was my mantra for the first 6 months when I was learning Smalltalk. Like most programmers back then, I had a background in procedural programming and it was very difficult to shake that mindset. Here's where the infamous paradigm shift comes into play. The Transcript is an object, the menus on the transcript are objects, the buttons on the transcript are objects, the Workspace is an object, etc. But before we get into that, let's start with the venerable 'Hello World' example:

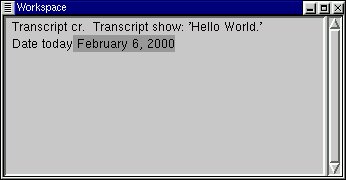

Ex 1: Hello World

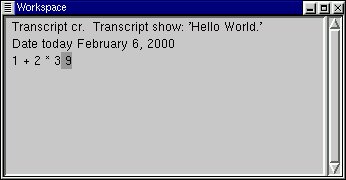

- Open a new workspace (click on Tools>Workspace)

- In the workspace, type: Transcript cr. Transcript show: 'Hello World.'

- Congratulations, you just wrote your first Smalltalk code. Now let's see it work:

- Highlight that line of code, middle click and select do it (This evaluates the Smalltalk code you just wrote)

- You should see the 'Hello World' text be printed in the Transcript:

Fig. 4 - Hello World example- Let's examine the Smalltalk code:

-

| Transcript cr. |

This code gets a hold of the Transcript object, and asks it to show a carriage return on itself. |

| Transcript show: 'Hello World.' |

Gets a hold of the Transcript object, and asks it to show 'Hello World' on itself |

- You can also print 'Hello World' to the command line, open a new window and print 'Hello World' on it, or design a GUI and put 'Hello World' on it. But again for the sake of brevity, we'll move on.

- cr is a message to Transcript, just as show: is a message to Transcript too. They're just messages that Transcript knows how to respond to. They're not part of Smalltalk syntax.

- The above point is important to remember for the non-OO programmers out there, we send messages to objects to ask them to do something.

Realize that you just executed your first Smalltalk code without compiling. You didn't have to save your code, compile and link it, and then run it. "So what, it's an interpretive language" you say. Well, not really. To be more precise, it's an incrementally byte-compiled language. I'll come back to this in a bit. For now, just be aware that you're coding and executing in Smalltalk seamlessly. Now, on to the next example:

Ex 2: Displaying current date

- In your opened workspace, type: Date today

- Highlight that line of code, middle click and select print it (This evaluates the Smalltalk code you just wrote, and prints out the result.)

- You should see the current date printed, like:

Fig. 5 - Printing Date today

-

| Date today |

Asks the class Date what the date today is |

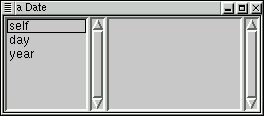

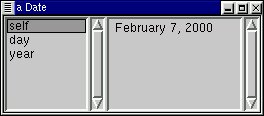

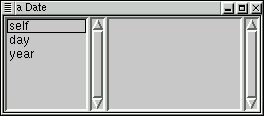

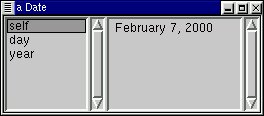

- Ok, let's get a better look at what Date today is evaluating to. Highlight that line of code (without the date that was printed), middle click and select inspect it. You should see:

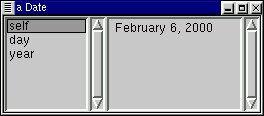

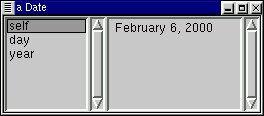

Fig. 6 - An inspector on a date- This is called an inspector (This too is an object BTW). Inspectors are objects that allow you to have a peek at objects. If you click on self in the inspector, you'll see a textual representation of the date:

Fig. 7 - Inspector showing textual representation of the date- Look familiar? That's because in Fig. 5, when you printed the Date today, you were really printing a textual representation of the Date object. If you click on the two other attributes of this date, you'll see that day keeps what day number it is within the year (1->365, usually), and year keeps what year the date is for.

- All objects have a textual representation, even if it's just the type of object it is (though that isn't very useful).

- The inspector is a very powerful concept. Realize that you just asked Date for the current date, and you got a hold of a date object. You can not only peek around this date, but you can also work with it and modify it. For example, click on day, and enter in n+1 for what is there. In Fig 7, Feb 6 is the 37th day of the year, so I'll enter in 38. Then middle click, and choose accept. You'll notice that it appears that nothing has changed. But what you've done is to now set the object to represent the date for the n+1th day of the year. Now, if you click back to the self on the date, you'll see it's now showing a date for one day later than what the current date is:

Fig. 8 - Inspector showing date after current date

So, not only can we write code and immediately execute it, but we can grab hold of objects, and manipulate them directly with immediate effect. These two abilities is part of what makes Smalltalk such a productive environment. You can code-n-test in real time. If you don't understand what's going on, you can just grab an object to see what its state is, and manipulate it to see how it behaves. After a build, if there's a bug in testing, you can quickly code in a fix and just load it into the testing environment - no need to recompile.

Another thing to notice is the literateness of Smalltalk. To get the date today we just asked Date for today. Though Smalltalk is a very literate language, it obviously has to break down somewhere, for example, we can't ask Date for tomorrow. That being said though, the general syntax of Smalltalk is very simple and easy to read. Keep this in mind while looking through the upcoming code examples.

Let's move on to the third example of this section then, and get into the paradigm shift aspect of OO:

Ex 3: Illustrating the paradigm shift

- In your workspace, type: 1 + 2 * 3

- Now, before you evaluate this code, think about what the answer is going to be. You're probably thinking 7. Well, highlight the line of code and print it

- You'll notice the answer is 9:

Fig. 9 - Result of message send- It's funny how many non-OO programmers go running in tears after I show them this. "What! No operator precedence, what a foul language! I'm going to stick to C++ because I can understand it!" Seriously, I've had it happen many times.

- However, reality depends on the blinders you're wearing; when I wrote the answer above, I first thought of writing 9, because I was thinking in an OO mindset, not a procedural mindset.

- The reason this is the case, is because (repeat after me) everything is an object. In this example, the numbers 1, 2, and 3 are all objects. The operators: + and * are just messages that are being sent to objects. The reasoning is that if + and * are just messages, why should they have precedence over other types of messages? All messages of the same type are treated equal in Smalltalk.

- To see for yourself, highlight 1, middle click, and choose inspect. You'll get an inspector on SmallInteger, which is the type of object that the object 1 is.

Fig. 10 - Inspecting the object 1- So, the code is evaluated as:

-

- (the number 1) is asked to do (+) with (the number 2)

- (the number 1) does this, answers the object: (the number 3)

- (the number 3) is asked to do (*) with (the number 3)

- (the number 3) does this, answers the object: (the number 9)

- To get the code to evaluate as a procedural mindset would expect, you can use brackets: 1 + (2 * 3)

- "OK, why can't I highlight the date I printed, February 6, 2000, and inspect that to see the date object?" Good question. The simple answer is that there are certain types of objects that can be brought into being (instantiated) by just inspecting a textual representation of them, and there are certain types of objects that can't. Integers are one of those types of objects that can be instantiated by inspecting a textual representation of them.

4.0 Incremental byte compiling

As I mentioned before, Smalltalk is an incremental byte compiled environment. Some people describe it as being a cross between compiled and interpretive languages. What happens when you do or print something, is:

- the Smalltalk compiler translates the Smalltalk code into byte codes

- the byte codes are passed to the virtual machine for execution

- the byte codes are executed, and the result is returned

Well, this sounds rather interpretive, doesn't it? The difference is that what we've been doing so far isn't normal Smalltalk programming. Recall that Workspaces are just a temporary sandbox. Normally, when you're programming, you accept Smalltalk code (save it in the image), and the code stays byte-compiled. Normally, when you're programming, you accept Smalltalk code in methods for a class, and:

- the Smalltalk compiler translates the Smalltalk code into byte codes

- the byte codes are kept with that class

- when a message is sent to a class, the appropriate byte codes for the method are sent to the virtual machine for execution

- the byte codes are executed, and the result is returned

The net result is that every time you make a change to your classes, that small change is semantically checked, is compiled, and takes effect immediately. It's pretty cool to make a tiny change, then see it immediately reflected in your program's behaviour.

Java is similar in the respect that it is byte compiled, but different in the respect that it isn't incrementally byte compiled. So when Java programming, you need to recompile all of it (or parts of it if you're using make), and relink all of it every time you want a change to take effect.

5.0 Virtual Machine/Portability

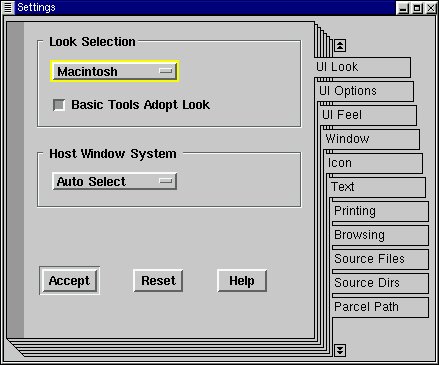

The virtual machine is just what it sounds like - a virtual computer that knows how to execute Smalltalk bytecodes. The virtual machine is usually implemented in C (squeak is the notable exception to this, even its virtual machine is implemented in Smalltalk - then exported to C programmatically). It's the virtual machine that allows for such portability across different machine types. Smalltalk has had the write once, run everywhere paradigm for decades! To give you a quick taste of this, select File>Settings. In the Dialog that pops up, select the Look Selection of Macintosh, then select Accept.

Fig. 11- Selecting a Mac look-n-feel

Now you'll notice that your entire system is running with a Mac look-n-feel! The first time I saw this back in '95, it blew me out of my chair. I had just spent a year doing a very painful port of OpenWindows to Motif for parts of a C based application. Then, here somebody showed me how they could 'port' their application from SunOS to Solaris to MacOS with a click of a button!

Fig. 12 - Transcript with Mac look-n-feel

Keep in mind that the above window is running on a Linux box! I commonly use this feature at work when my employer is developing in Windoze, because I prefer the Motif look-n-feel.

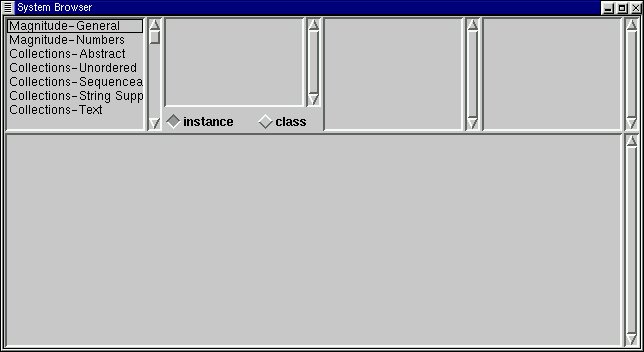

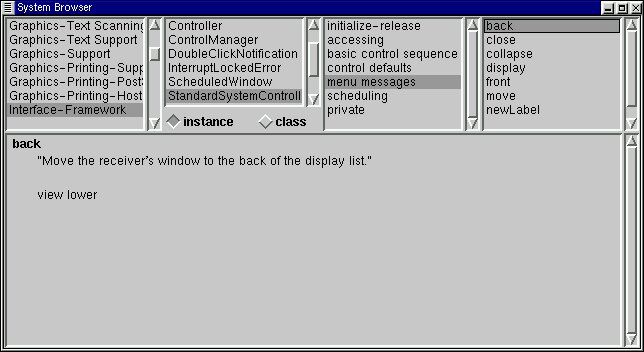

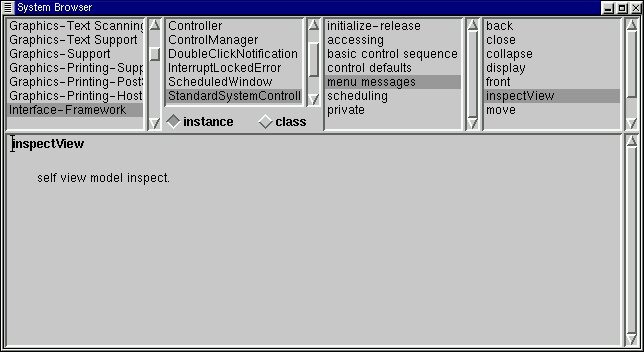

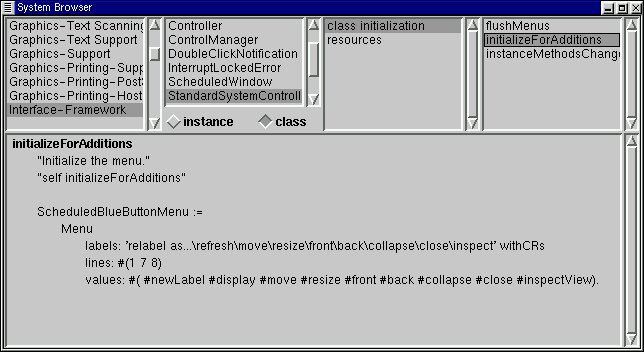

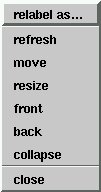

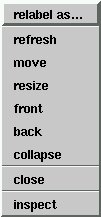

6.0 Reflectiveness

Here's where I think the real power of Smalltalk comes to play: in its reflectiveness. In Smalltalk, 98% of Smalltalk is written in Smalltalk, which makes it easy to customize, enhance, or tweak the environment. (Squeak is the notable exception here, 100% of it is written in Smalltalk). So it's very easy to see how Smalltalk is written, and to extend it for your needs. In fact, this is the whole basis of development in Smalltalk. You start with a running application, you add business-specific extensions to it, strip out the parts you don't need, and then deliver the running application. Here's a simple example to show how to extend Smalltalk:

Ex 4: Adding inspect menus to all windows

Note: What we just did here was a base image extension. This is a type of coding change that should be done and tracked carefully.

7.0 Garbage Collection

Yea, though I walk through the valley of doomed schedules, I shall fear no deallocating...

Garbage collection: AKA the sanity saver. Smalltalk has garbage collection, which means objects that are no longer referenced are cleaned up to free up memory. I remember pulling out my hair many a time when programming in C++ trying to find memory leaks. This is because in C++ it's up to the developer to manage your memory. If you didn't deallocate the memory you're using, your application would continually take up more memory until your machine ran out of memory and crashed.

Speaking of machines crashing, you'll note that we never had to do any pointer manipulation. This is because Smalltalk has no pointers. (Well, this is technically incorrect. Every variable reference is actually a pointer to an object, it's just that in Smalltalk the developer is relieved of the burden of manually maintaining pointers).

8.0 Summary

I hope that I've been able to give a concise, meaningful tour of Smalltalk that has been approachable by non OO programmers. I've shown that Smalltalk:

- is a pure OO environment, encourages OO programming

- can save exact state of the IDE

- is a literate language

- is incrementally byte-compiled

- is a portable environment; write once, run anywhere (virtual machine/ GUI)

- can inspect and manipulate objects in real time

- has a large degree of reflectiveness (start with running app, extensions)

- has garbage collection, no explicit pointers

There's lots of other cool things I would liked to have touched upon in this article, but space constraints just don't allow for them:

- the online help

- debugger

- numbers - (try printing 100000 factorial in a workspace (if you have the time for crunching - number size is only limited by your memory), or try inspecting 12/7)

- parcels - a code sharing mechanism

- Refactoring Browser - my favourite programming tool

- HotDraw - a reusable draing framework

- testing frameworks - automate your testing

- dynamic changing of widgets at runtime

Glossary

| Category |

A group of classes |

| Class |

A type of an object |

| Horizontal market |

A market that tends to have a very large audience and has a very small impact on that audience. Shinkwrapped software addresses a horizontal market. For example, a word processing package - if it crashes, just reload your last saved snapshot. |

| Inspector |

A GUI type of object that allows you to look at and work with objects. |

| Literateness |

A simple definition of literateness is how readible/simple the syntax of a language is. Literate programming is programming for readability for the programmer who comes after you. |

| Method |

A piece of Smalltalk code for an object. |

| Object |

A grouping of related data and operations. It exhibits behaviour through its operations on its data. |

| Protocol |

A group of methods. |

| Reflectiveness |

How much of an environment can be manipulated within itself. In Smalltalk, 98% of Smalltalk is written in Smalltalk, which makes it easy to customize, enhance, or tweak the environment. (Squeak is the notable exception here, 100% of it is written in Smalltalk). |

| Transcript |

The main window of the IDE, where other windows (browsers, workspaces, etc) are opened from. Also keeps a running list of system messages. |

| Workspace |

A scratchpad where developers can experiment with code. |

| Vertical market |

A market that tends to have a very small audience and has a very large impact on that audience. For example, a network management system for a telecommunications company - if it crashes the company loses a million dollars a minute. |

Further References

- A history of Smalltalk

- A brief history of Smalltalk

- GoodStart

- WikiWikis:

- Smalltalk

- Squeak

- VisualWorks

- Newsgroup: comp.lang.smalltalk

- Free Smalltalk archives:

- Smalltalk (UIUC - the granddaddy of Smalltalk archives)

- Squeak

- VSE (in German)

- Tutorials:

- Squeak

- VisualWorks

- Lots 'o Smalltalk Links

- Dave's Smalltalk FAQ (There's a number of ones out there, but even though it's dated, this is the best IMHO. Dave - it'd be great if you ever got time to finish this.)

- eXtreme Programming (Which originated in a Smalltalk project)

Footnotes

- Every implementation has different license restrictions. To my knowledge, only GNU Smalltalk and Squeak have GNU copyleft types of licenses.

- The last two implementations are the newer ones.

- In article: http://x37.deja.com/getdoc.xp?AN=564595555&CONTEXT=949863157.89849870&hitnum=0

Author:

Eric Clayberg

<[email protected]>

Patrick Logan <[email protected]>

wrote in message

news:[email protected]...

>

> I wish the original Oak team had chosen to adopt Smalltalk

> rather than invent Java

They tried to, but ParcPlace wanted too much on a per-copy royalty basis...sigh

- Bah! Real programmers reinvent the wheel all the time, it puts hair on your chest! ...sigh, I've run into that far too many times over the years. More often than not, the wheels that are reinvented tend to be rather square. Too bad that schools often encourage this mentality during formal training. [End soapbox]

- This is some loose terminology that shifts depending on who you're speaking with. For my purposes, an Object based (OB) language is a non-OO language that has been evolved towards Object-orientedness. (C++, OO-COBAL, etc). Some people call these bastardized OO languages.

- Some productivity numbers from Software Productivity Research. (A sample of ave. source statements/function point: Smalltalk: 21, C: 128, C++: 53, Visual Basic 5: 29)

- GoodStart - who's using Smalltalk - http://www.goodstart.com/whoswho.html

Copyright © 2000, Jason Steffler

Published in Issue 51 of Linux Gazette, March 2000

Talkbacks

![[ Table of Contents ]](../gx/indexnew.gif)

![[ Front Page ]](../gx/homenew.gif)

![[ Prev ]](../gx/back2.gif)

![[ Linux Gazette FAQ ]](./../gx/dennis/faq.gif)

![[ Next ]](../gx/fwd.gif)

![[ Table of Contents ]](../gx/indexnew.gif)

![[ Front Page ]](../gx/homenew.gif)

![[ Linux Gazette FAQ ]](./../gx/dennis/faq.gif)